Bodybuilding, Powerlifting, and Other Training Styles

Learn about different types of strength training, including bodybuilding and powerlifting. Discover how to create a bodybuilding program and track your progression over time. Also, find out the cor...

16 min read

Bodybuilding

The goal of Bodybuilding is to create a larger and more symmetrical figure. This is accomplished best through intelligently designed programming that accommodates the athlete’s availability, goals, & experiences. Bodybuilding doesn't have to entail getting a fake tan & going up on a big stage; it can just be aiming to look better over time. If you're serious about optimizing your progress, you should probably get a coach. However, for the sake of people who can't afford a coach or simply want to learn or refine their knowledge, I’ve done my best to include as much information as I can to in this guide to help you maximize symmetrical muscle growth.

It's all about muscle growth.

Here are 3 general outcomes of resistance training:

Mechanical Tension

Metabolic Stress

Muscle Damage

Our purpose in training is to grow muscle as fast as possible for as long as possible. Despite common belief, muscle damage & metabolic stress absolutely do not cause muscle size growth, AKA hypertrophy. I could run a marathon, filling my body with metabolites such as lactic acid or literally damage my muscles... neither of these will induce any significant hypertrophy. Therefore, with these other outcomes from resistance training clearly ineffective for muscle growth, mechanical tension comes out on top as the primary driver of hypertrophy.

People adapt to ‘old’ mechanical tension, making the exact same rep/weight/set plan less effective for growth over time. Therefore, in order to ensure that someone is progressing, they should strive to achieve something called 'progressive overload.' This can be defined as a consistent increase in some form of training metric over time. In the interest of training consistently for lengthy periods, we want to minimize fatigue & risk of injury. Thus, we should only use as much volume as we individually need to progressively overload over time & also be sure to also warm up properly.

Mechanical Tension & the Stimulating Reps Model

As we train harder throughout an individual set, different muscle fiber types activate within each muscle group involved.

The low threshold Type I fibers, which consume oxygen as fuel, activate initially.

As our intensity ramps up, the Type II/IIx high threshold fibers activate. These consume glycogen stores within our muscles. These fibers undergoing hypertrophy accounts for most of our long-term muscle size growth.

Relevant mechanical tension in the important high threshold fibers, type II/IIx, only occurs around the last 5 reps before failure in a set. These can be termed as 'SRs' or stimulating reps. One key part of SRs is the clear reduction in contraction velocity. Simply put, the concentric part of each rep should be clearly slowing down near the end of each set, no matter how hard someone pushes. Also, Stimulating Reps requires reaching a lengthened position, such as at the bottom of a squat. This is due to the pathways by which force output is created in each muscle fiber.

Some general pointers:

The type I fibers are also fully stimulated at a sufficient stimulating reps count.

On average, people seem to benefit most from 15 to 30 SRs, ideally done ~2x weekly.

It is false that the last rep before failure is much more stimulating than the prior 4 SRs.

Stimulus is less effective throughout a workout due to increasing fatigue & decreasing energy.

This model has been spearheaded by Chris Beardsley & Borge Fagerli, among others.

The 'Formula' for Maximized Muscle Growth:

Great Training Stimulus

Train very hard, but not to failure every single set, so that you can train your groups ~2-3x/week.

Use just enough sets/volume while training hard to induce progressive overload. This means consistently increasing some form of training metric, such as rep count, weight, or form quality.

Rest until you're mostly recovered each set (commonly 2+ minutes) and don't consecutively train the same muscle group.

Increase volume slightly, swap exercise, alter rep range, or incorporate an intensifier when you plateau.

Deload only when necessary.

Proper Diet

Base a surplus around your capacity to grow muscle at your current stage of lifting to avoid unnecessary fat gain. Male beginners: 350-600. Intermediate-advanced trainees & women: 150-350.

Spend long periods in your dietary phases (think months, not weeks).

0.8+ grams of protein per lb (1.65g/kg) bodyweight daily & more while in a deficit to attempt to maintain more muscle & utilize its properties of TEF & satiety.

Consume electrolytes & food before your sessions so that you maintain fluid equilibrium & allow the glycolytic type II fibers to produce force effectively.

Ideally, split protein into 4-5 meals daily.

Aim to drink 2.7-3.7L+ water throughout each day; use electrolytes amply.

Good Environment for Recovery

~8 hours sleep without interruption within the same timeframe daily.

Manage & work on stressors in your life.

No caffeine 6-12 hours before sleep. Eliminate or highly limit use of alcohol/recreational drugs.

Stages of Training

Beginners tend to make progress with the amount of weight added to their exercises (progressively overload) weekly, whereas intermediate and above level lifters tend to require much longer to progress. This further depends on their diet phase and other contributing factors, such as stress, sleep, etc. For example, if an intermediate lifter is in a significant caloric surplus, they may be able to progress weekly, & then make very minimal progress while in a deficit. Hopefully, this concept of how fast you progress can help you determine what stage of lifting you’re at. People progress at different rates and have different starting points muscularly, so the time frame for progress looks like a spectrum as such:

Beginner: 0–2 years strength training

Intermediate: 1–4 years

Advanced: 2–10+ years

"Newbie" Gains

Consider this metaphor: the deeper you dig a hole, the harder it gets to dig. It doesn't matter how fast you dig a hole, but you do progressively find more difficult material to dig deeper down. Fitness progress is much like this. It plateaus over time, but this plateau isn't truly based in nature on a specific time frame. Point being, no one should ever stress over the losing the opportunity to get their 'beginner gains' due to time constraints.

Beginner Training / Bodybuilding

For beginners, I recommend starting with a training split lasting 3-5 days per week. It is much better to choose a 3-4 day split instead of commonly skipping days on a 5-6 day split. I trained till failure when I started, a large mistake in my case; doing so resulted in an injury that needed physical therapy & prevented me from training for 2-3 weeks. Needless injuries like what I experienced can be prevented by avoiding training to failure, especially when first starting out or returning to a resistance training program. This will likely lead to equal growth in beginners (vs. failure) with the additional opportunity to make progress in technique over time. It's okay that beginners don't truly understand what 2rir (reps in reserve) means because they'll still be targeting low threshold muscle fibers in any case. Soreness is a large topic of discussion in beginners, so I’d like to make a couple things clear: soreness becomes much more manageable after the initial sessions of a routine. Soreness & muscle damage do not cause muscle growth! They are simply a byproduct of muscle stimulation.

Intermediate Bodybuilding

The longer a person lifts, the more they benefit from taking sets closer to failure (though they then must be more cautious with fatigue/muscle damage buildup). This is due to the fact that they have already grown most of their potential capacity of low threshold slow twitch (Type I) muscle fibers during their beginner phase of lifting. And thus, they must train harder (0-2rir, logically) to develop the higher threshold fast twitch muscle fibers (Type IIA/IIX) and continue making serious progress. Ideal stimulus for intermediate bodybuilders may differ significantly from person to person. The best approach is to start at a lower-end volume & then determine progressive overload is occurring throughout 3+ weeks. If not, add a little bit of set(s) to your weekly goal per muscle group, and re-evaluate over time. Someone should repeat this process until they find what ‘volume,' or really how many effective reps, suits them best. My bodybuilding programs offer this function, along with rep range customization (which could possibly lead to different amounts of growth in each athlete's individual muscle groups) in full. You can also experiment with lengthening the days of rest between your sessions, such as utilizing PPLR or PRPLR splits, which function independently of weekdays, (unlike 7-day weekly splits) to accommodate for how long you need to recover individually.

Advanced Bodybuilding

The concept causing the most problems for upper-level trainees is the faulty idea that, as someone gets more advanced, they need more volume. This is absolutely not the case; the more advanced someone is, the greater their capacity for motor recruitment from less sets & the greater fatigue they face per set. Most highly advanced bodybuilders use & benefit most from a modified bro split where they stimulate each muscle around once a week. This later stage of training necessitates extremely hard & intentional training to obtain any further relevant stimulation and, oftentimes, full on coaching.

Training to Failure

In resistance training, failure should be defined as the inability to complete another full range of motion repetition on any given exercise. In all levels of trainees, training to failure can be a very valuable tool to approximate old sets' RIR (reps in reserve). In that context, failure is best placed only at the end of a program. In the literature, it seems clear that when you tell a beginner to train to failure, they end up growing the same amount of muscle as if you told them to train to 2 RIR.

As mentioned previously, intermediates & advanced lifters must train harder to continue making progress. Volume and intensity have inverse relationships; for example, when you increase intensity, you should also reduce volume. The goal in all scenarios, however, appears to be around 15-30 Stimulating Reps per session. That's an averaged number per muscle group per session and it assumes that someone is resting sufficiently. The goal for everyone should be to minimize fatigue while maximizing stimulus, and this has some relevant considerations:

These Stimulating Reps do not have to be achieved by muscular failure; that last 5th effective rep at failure is significantly more fatiguing than the previous 4. SRs are also less effective as a session stretches on due to increasing fatigue.

When utilizing exercises with larger muscle groups & doing sets with higher rep ranges (ie. squats at 15-30 rep range) there is a significantly larger buildup of metabolites. This makes someone feel as though they’re closer to failure then they truly are. Therefore, higher intensity goals potentially should probably be paired under those aforementioned conditions.

Muscle Imbalances

Many people suffer from muscle imbalances. There are a few different kinds of muscle imbalances. There is a variation in the actual muscle insertions–this is entirely normal. There is also variation in the overall development of an athlete's muscle groups–an issue that needs correction in bodybuilding. This can be variation from the left to the right sides in size or a lacking muscle group compared to others on the same athlete (ie. legs vs back). The solution for most beginner-intermediate lifters lies simply in consistently training with no change in routine. If someone has a left vs right side imbalance after the early intermediate stage, they should consider utilizing unilateral exercises and doing the weaker side first, then repeating the same amount of reps for the stronger side. If they minimize the rest time between left vs right further disadvantages the motor recruitment on the dominant side due to various forms of fatigue. On the other hand, if an entire muscle group is lacking compared to other muscle groups, someone should take measures accordingly: first, verify that the group is properly recovering between days and that your form/execution and intensity are perfect. Then, if those basic practices are not fruitful, implement these protocols one at a time, in descending order:

Place the exercise(s) for the lacking muscle group earlier in the session.

Add a small amount of volume (1-2 sets) to the group for your mesocycles.

Consider a periodized approach where you consistently increase the weekly volume goal for the lacking muscle groups exercises. This approach certainly forces deloads and might be risky for connective tissue, but it might be effective for some people.

Deload Phases

In training, deloads are a fatigue management mechanism that allow both connective & muscular tissues to fully recover while resetting persistent fatigue buildup. They can be accomplished by either quitting the gym for a week (not recommended, leads to limited strength gains) or by reducing goal set count & intensity for a week. Generally, you should halve the weekly sets and reduce the weight by 20-30% whilst maintaining the same rep goal(s).

Because beginners generally don’t understand systemic fatigue enough to know when they need a deload, they should have set deloads at, for example, every 8-12 weeks in their programming.

However, intermediate and above level lifters are certain to benefit from watching out for signs that they need to deload from their body to maximize training length before deloading. This might be anywhere from 3-12+ weeks, even possibly never, depending on the individual and various program factors. A few signs that you might need a deload include, but are not limited to: inability to get sore, prolonged lack of physique progress, and the inability to continue progressive overloading.

Paul Carter, a rude yet intelligent mind of the fitness industry, accurately claims that deloads are not an essential practice in every trainee when volume is reduced properly to the amount needed for progressive overload in that individual. On the other hand, Doctor Mike Israetel of Renaissance Periodization utilizes consistently increasing volumes throughout periodized mesocycles; this requires deloads very often. The fitness community has found that both approaches work. There is a preprint study available now that determined the following: in 9 weeks, similar muscle growth occurred when between a group who deloaded & one that didn’t. However, the participants were training at a very low frequency, so I don’t think it offers any pertinent information.

Acclimation Phases

An acclimation mesocycle is a training protocol to potentially reduce risk of injury & soreness from the first week of training. They should only be used when someone is returning to the gym after a break or changing from a low frequency/intensity split to a more difficult one. An acclimation phase appears identical to deloads in my training protocols, despite serving a different purpose.

Bodybuilding Programming

While anyone can make a program & still make a fairly strong amount of progress with it, it would simply be smarter to simply choose something that actually works and, at minimum, has science supporting its structure. If you really want to make bodybuilding programs for yourself or your friends, I highly recommend following these essential principles:

Train hard (0-2RIR) & consider your volume or effective reps count:

Start at the a lower end of the volume range & watch if progressive overload is occurring (more weight over time at the same intensity)

If it is, continue as normal

If progressive overload is not occurring, add 1-2 sets to the target group set count.

Stick to the same exercises for long periods of time. If one exercise has been plateauing in weight for 2-3+ weeks, consider changing it out.

Training Variables

Volume, rep ranges, rest times, exercise selection are all factors that may significantly vary between athletes and the individual muscle groups on their bodies. In order to optimize growth, it is absolutely necessary for someone to experiment and determine what factors they grow best from. However, this requires admitting that your previous approach may have not been ideal, a difficult yet essential step to take. All of the following values are averages based on the scientific literature available at this time. It is entirely possible that someone could vary significantly from what the literature supports, though it may be somewhat unlikely in reality.

Volume

15-30 effective reps or 5-10 sets at 2rir intensity/3-6 sets @0rir per muscle group per session.

Recognize that synergist muscles (ie. biceps in rows) receive relevant stimulus in non-isolation movements. I quantify synergist muscles as receiving ½ a unit of stimulus (set or stimulating rep)

The more advanced you are, the more type II muscle fibers you have, the less volume you need for a great stimulus.

All relevant muscle groups include: delts, chest, back, biceps, triceps, abs, hamstrings, quads, and calves. These all require their own stimulus and count as their own muscle groups. The legs are separated because of how large they are, though smaller muscle groups like calves and abs might not need as much volume as other groups.

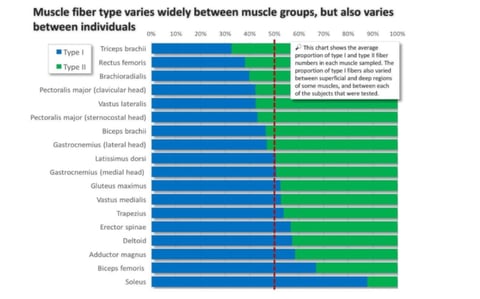

On average, the triceps, brachioradialis, biceps, pecs, and gastrocnemius are Type II fiber dominant. This varies between people but it can be assumed that, on average, these muscles therefore tolerate slightly less volume to yield the same quality of stimulus.

Abs, Calves, Traps & Forearms

There are many long standing myths around the training of these muscle groups. For example, people claim that they primarily benefit from higher rep ranges & aerobic exercises; they do not. In order to stimulate significant muscular growth, a muscle group must be taken near or to muscular failure within 5-30 reps throughout multiple sets with dedicated rest time between sets, generally. These groups are just like any other muscle on the body & should be treated as such. Do not train these groups every day; they, too, require days of rest in order to grow from stimulation. Localized fat loss through exercise of these muscle groups is also a myth; notable change only comes with reduction of total bodily fat or through muscle size growth. A couple examples of weak muscle growth stimulus would include: circuit style abdominals training or calf raises each step on a cardio machine. Here are some considerations for implementing these groups into a program:

Abs: Avoid training abs on the day before leg day. Note that someone cannot train individual ‘divisions’ of the abdominals (ie. upper vs lower); they all work together.

Calves: Focus on the eccentric portion of each rep with a lengthy tempo & by pausing in the lengthened position, where your toes are higher than your heel. The calves consist of the gastrocnemius & soleus muscles which are targeted with standing/leg press calf raises & seated calf raises respectively.

Traps: Physiologically, due to the way the trap fibers align throughout the back, high cable rows align much better with the traps than shrugs do. Because of the tiny ROM, shrugs are also challenging to take near proper failure.

Forearms: Avoid training forearms on the day before a back/bi day. Note that grip crushers don’t improve bar grip strength, rather simply crushing grip strength. These are easily trained with weighted wrist flexion & extension.

Powerlifting

Powerlifting training focuses on increasing the amount of weight performed in squat, bench and deadlift during competitions. In order to increase competition performance, powerlifters work on improving technique, muscle size and the ability of that muscle to produce force. Typically, powerlifters use a phasic structure of training whereby they employ mesocycles/blocks to organize their training and outcomes. These phases tend to include 3 types of blocks: hypertrophy, strength and peaking. Someone prioritizing neural adaptation and form improvement might employ 2-3 strength building blocks per 1 hypertrophy mesocycle, for example.

I'm not ready yet to create powerlifting programs, but it is something that I'd like to achieve in the far future.

Strength Building Mesocycle

A strength building mesocycle is a phase focusing on increasing your strength primarily via work on the 3 lifts and a minor amount of accessories as well. You should be training at RPE 6-8 for the majority of the mesocycle, possibly higher for accessories.

Hypertrophy Mesocycle

This mesocycle focuses on increasing the size of your muscles so as to lift more in the future. Ideally, you should continue doing the SBD lifts so as to maintain your strength. For example, the intensities of a hypertrophy mesocycle in an intermediate lifter might be RPE 6-7 for SBD and then far higher for your accessories, so as to optimize muscle growth. Any powerlifter who has never focused on hypertrophy is probably missing out on a lot of lift improvement.

Peaking Mesocycle

Peaking in powerlifting is a method to perform better than you usually would on your competition date. This can be accomplished by increasing your training RPE throughout 4-8 weeks. Overreaching is an essential part of Peaking and can be accomplished by doubling the volume of your routine from 14-7 days out from your meet. The final week should consist of no heavy work such as RPE 6-7 triples, for example. Peaking mesocycles offer minimal growth and should only be used when in meet prep.

Powerlifting / Programming Terminology

RIR/RPE

Reps in reserve designates the number of reps you could have done if you continued doing more reps in your set. 0RIR, for example, is muscular failure. RPE or rate of perceived effort is the opposite of this system numerically. Something RPE 1 would be 9RIR, or RPE 9 1RIR. These terms are essential in growth for intermediate and advanced lifters. They can even be a useful tool for beginners. Note that using halves in RPE is common ie. RPE 7.5, 8.5, etc.

Sticking Point

A sticking point is a place where someone struggles abnormally on their lift. There are many factors that determine these and often a coach is integral in determining and fixing these sticking points as fast as possible. For example, if someone struggles with locking out on deadlift, they may have insufficient glute strength/size. I plan on adding more information on these soon.

Top Set

This designates the set where you move the most weight of the day. This set will have the highest RPE of the day or may be equal to the backoff set(s) RPE.

Back-off Set

Back-off sets are utilized after a top set, as strength drops significantly each intense set you do. A standard value to drop the weight by is around 5-12% to maintain the same RPE at the same rep range. That value is primarily dependent on RPE.

Microcycle

A microcycle is one rotation of a mesocycle/block. These might be anywhere from 3 to 14 or more days, depending on the program. That being said, the vast majority of microcycles last a week.

Mesocycle/Block

A mesocycle or training block is multiple microcycles placed together to create an intelligent progression scheme. These tend to last 2-12 weeks.

Macrocycle

A macrocycle is typically 2-4 blocks of training, all with differences. That difference may be a different goal or a different style of progression, but all of the mesocycles/blocks should be performed congruently (albeit with a set amount of deload(s) relevant to consider as well).

LWU: Last warm-up (set)

This term designates someone's last warm up set. Who wouda guessed?

Great SBD Variations

Squat: Paused Squat, Pin Squat, Box Squats

Bench: Extra Long Pause Bench, Close/Wide Grip Bench

Deadlift: Paused DLs, Block Pulls, Deficit Deadlifts (don't do deficit DLs please)

Great SBD Builders

Squat: Belt Squat

Bench: Dips, Chest Press

Deadlift: RDL, SLDL, Weighted 45 Degree Back Extensions

Calisthenics

Calisthenics is a method of training using little to no equipment for calisthenics skills development and/or muscle growth. I am very inexperienced at developing calisthenics skills, such as muscle ups, so I have little to offer on that topic right now. However, I am well experienced in the progression of calisthenics movements for the purpose of muscle/strength growth. You can find my beginner-intermediate calisthenics program below. It explains everything; I bet it will be unlike the vast majority of programs you find online.

Calisthenics Equipment

In order to get decent stimulus for your muscles at home, you absolutely need to have equipment or weight of some kind to use. That could be a 10lb dumbbell, or a couple water jugs, heavy books, or something else in a backpack; you have to be resourceful. You also need a pullup bar, but if there’s a safe handhold somewhere in your house, at the playground, or elsewhere, that works as well. Some parallettes from amazon or elsewhere could be useful for pressing movements, such as dips or pull ups.

Other Training Styles

Crossfit

Crossfit is a very popular method of training for one simple reason: it has perfected creating the runner’s high with as little work as possible. The runner’s high is something of a euphoric state caused by a large release of endorphins; crossfit combines strength training and cardio exercise while minimizing rest time between exercises & achieves the ‘runner’s high.’ This is not a logical training methodology because basic muscle growth concepts necessitate both rest time between sets and a scenario where you can push yourself near muscular failure. The progress made in cardiovascular exercise suffers just as much as the muscle growth. It is undoubtedly best to separate these training protocols to maximize results.